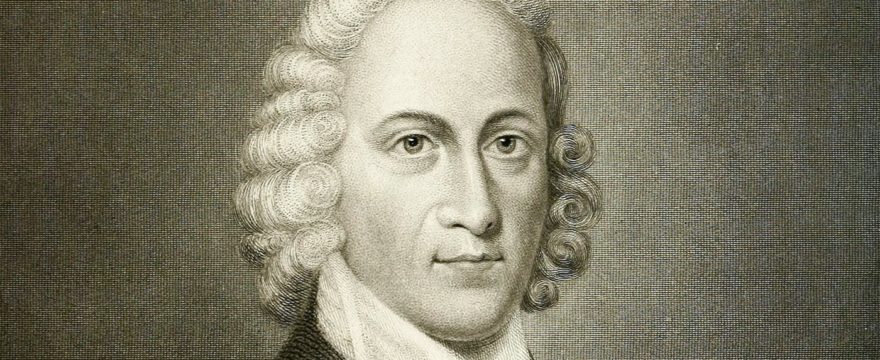

First Published: A Short Life of Jonathan Edwards, George Marsden, Eerdmans Publishing, 2008 (ISBN 978-0-8028-0220-0), vi + 152 pp., pb $15.00

Individually, these books are an informative look at two influential thinkers in American religion. Together, they serve as bookends to a period of American history in which Evangelicalism emphasized a particular perspective of soteriology that minimizes the intellect. What makes this such an interesting study is that both Edwards and Schaeffer made significant use of the intellect as opposed to much of what goes on between their times. In some sense, Jonathan Edwards set the standard for American intellectual religiosity so that much of what comes later is compared back to him on that plane. On the other hand, Schaeffer is credited as reinvigorating the life of the intellect among Evangelicals, and many of the Christian scholars who work in America in the decades after Schaeffer trace their own motivation to his work. This is revelatory of how Evangelical American’s understand the ‘intellect’, both those who emphasize it and those who downplay it.

In A Short Life of Jonathan Edwards, George Marsden a shorter version of his earlier book on Edwards. This shorter version is accessible and encouraging to read. He proceeds through eight chapters, and presents the life of Edwards as a story of growth, challenge, and overcoming in a not only rough and difficult, but also young and budding, country. Perhaps what Edwards is best known for is his involvement in the first Great Awakening. As a pastor he had seen its benefits and its harms, and as an intellectual he was aware not only of the potential divisions that could arise but also of the need for greater understanding and commitment on the part of the colonials.

Marsden presents Edwards as beginning his intellectual inquiry with the assumption that God exists. ‘The core principle that many religious believers might take from Edwards is that, if there is a creator God, then the most essential relationships in the universe are personal. Edwards started every inquiry with reference to God. If we want to understand the universe, then we must understand why God would have created it’ (p. 137). Having read Locke, Edwards was aware of the kinds of proofs for God’s existence offered by that philosopher. But he also saw the greatest challenge against Christianity coming from deism which affirmed God the Creator while denying divine providence and the need for redemption.

Since that time, naturalism has overcome deism as the most common alternative to theism in America. ‘Such a grand vision of a God centered personal universe provides a sharp contrast to the essentially impersonal and materialistic view of the universe that has predominated since the Enlightenment of Edward’s day. Edwards was in fact directly countering the secularizing aspects of the Enlightenment trends that he saw around him. At the apex of the intellectual fashion of his day was deism’ (p. 138). The popularity of deism among intellectuals is a source of anti-intellectualism among the religious, who say that going down the road of the intellect leads away from Christianity to deism. This kind of argument has only become more popular since that time in that intellectuals (in large part) have abandoned belief in God as well.

Marsden argues that the argument Edwards gave against deism was to empathize the love of God. ‘The universe is, in other words, the result of the ever-expanding “big bang” (to use a later term) of God’s love. If we see reality in its true dimensions, then, we see it as an ongoing expression of the beauty of love flowing from the Creator. If we sense the beauty of the light coming through the trees or the flowers in the fields, we are capturing small glimpses of the beauty of God’s love. The physical world is the language of God; “the heavens declare the glory of God,” as it says in the Psalms. Sin has partially corrupted the universe and often blinds humans from seeing its true essence. Yet, for those who, through the work of the Holy Spirit, have their sight restored, they can see all of reality not as essentially impersonal but as, in its essence, a beautiful expression of God’s love’ (p. 137). Here we will need to do work to distinguish how much of this is Edwards and how much of this is Marsden. How much did Edwards emphasize the love of God over and above the other attributes of God? What about the justice of God? Certainly, Edwards is known for his teaching about this as well, in his sermon ‘Sinners in the Hand of an Angry God’. Perhaps what can be said is that Marsden, who is part of the group in America that owes much to Edwards and the evangelicals, is bringing to this study the evangelical stress on the love of God. It is also interesting to see in the above quote the phrase ‘partially corrupted’, which seems to deny the doctrine of total depravity in Calvinism and so probably is not correctly attributed to Edwards. It also seems to be a Reformed

Epistemology reading of Edwards which speaks of creation and redemption in terms of God’s love, rather than the actual Reformed tradition which speaks of creation and redemption as revelation of the glory of God (Westminster Confession), which glory includes many more qualities in addition to love.

Marsden traces the influence e of Locke and others on Edwards by locating him as an advocate of the Enlightenment. He does this in a way that shows how Edwards found room for God in what others took to be a mechanistic worldview. But once again he reduces this to the love of God rather than the glory of the totality of the nature of God. ‘Edwards, who was also impressed by the Newtonian understanding of physical reality, moved in just the opposite direction. Rather than viewing the physical world as essentially impersonal, he saw it, even in its scientifically predictable laws, as an ongoing and intimate expression of God’s love. Through God’s revelation of the redemptive work of Christ, fully disclosed only in Scripture, one could find the clues necessary for understanding a universe with personal love at its enter. Everything, when rightly understood, pointed to God’s redemptive love’ (p. 139).

Marsden notes that the second Great Awakening went in directions that would not have pleased Edwards. Yet, he also seems to have provided a groundwork for that direction: one begins with the belief that God and sin exist and presents Christ as the remedy for sin; the individual must be brought to make a choice to accept Christ as their savior and this can be done in many ways that were not used traditionally; if the intellect can be useful in this process, or can defend this message against critics, then it can be helpful. However, the intellect is not necessary because the focus is on going to heaven in the afterlife and this is achieved by accepting Christ, which is a choice that can best be produced by appeal to emotions rather than by giving intellectual arguments.

Consequently, the time after Edwards leading up until Schaeffer witnessed numerous ‘awakenings’, and even more new religious movements that relied upon Christian terminology but gave new meaning to that religion. In the intellectual realm, naturalism and its prophets such as Darwin, Marx, and Freud had come to rule the day. Thus, for Evangelicals, there seemed to be very little need for the intellect: the soteriological focus of their religiosity was not seen to need the intellectual, and the intellectuals of society were non-Christian or even anti-Christian. It is in this context that Schaeffer begins his work.

Having known something of Schaeffer’s work, I appreciated the Hankins volume for how it filled in the story of his life and ministry. In eight chapters, Hankins discusses the ministry of Schaeffer in terms of three stages. He links these to three kinds of admirers of Schaeffer: there is the conservative Evangelical, the Christian scholar, and the Christian involved in right-wing politics.

Even in light of the praise for Schaeffer, Hankins argues that he was too rooted in Enlightenment epistemology and metaphysics, and that this was a common failing among American Evangelicals. ‘American evangelicals have been shaped by the modern world that grew out of the Enlightenment at the same time they have often seemingly been at war with modernity. They have been aptly characterized as having “a love affair with the Enlightenment science.” But when the scientific worldview moved toward more theoretical forms of science, including Darwinian evolution, evangelicals and especially fundamentalists, were often caught flat-footed’ (p. 234). An alternative reading of this history might be that while the Enlightenment got some things right about reason, it also got many more wrong, and this lead to the rise of naturalism which was a response to these errors. The correction is not to be found in abandoning everything from the Enlightenment but in correcting where it did not go far enough. If it is assumed that the Enlightenment was correct about reason, then the rejection of the Enlightenment will be a rejection of reason and a resulting anti-intellectualism. If, instead, the Enlightenment is seen to have held inconsistently to ideals of reason, then we can continue to strive toward those ideals without abandoning reason and the intellect.

Schaeffer represents a kind of anomaly for evangelicals in that he not only did not fit into the anti-intellectualism of those preceding him, but he also did not emphasize the intellect and neglect the love of other. ‘In on respect Schaeffer stands as a significant exception to the scandal of the evangelical mind. He was one of those responsible for helping evangelicals reject fundamentalist anti-intellectualism in favor of a renewed emphasis on things of the mind and a reengagement with mainstream intellectual culture. Moreover, Schaeffer was intuitively gifted in understanding young people who had pushed the Enlightenment project to its logical conclusion, with its emphasis on reason alone as the way to the truth. Schaeffer knew there was no way to begin a rational argument without an assumption that something was true. In Schaeffer’s apologetic evangelism he put a personal God at the beginning of the reasoning process, then attempted to show that everything else made sense once that presupposition was adopted. By contrast, he argued, when the process starts merely with space, time and chance, nothing makes sense. The truly modern person must either smuggle meaning into his or her worldview or admit that life has no meaning. Schaeffer argued effectively that individuals could not live consistently with meaninglessness’ (p. 235). Like Edwards, Schaeffer begins with belief in God as necessary for meaning in the universe. Similarly, his emphasis on the need for meaning and the use of arguments is taken to be an abandonment of the doctrine of total depravity.

Hankins critiques Schaeffer for this emphasis on reason (and notes many others who also faulted him such as Cornelius Van Til, George

Marsden, and Mark Noll). The conclusion is that Schaeffer was helpful for his time but did not offer a lasting contribution because people are no longer interested in reason. ‘This argument seemed to work, although it seems that at times Schaeffer underestimated the degree to which the nonrational aspects of the Christian community of L’Abri were essential for the effectiveness of the message. For all of its strengths, the weakness of Schaeffer’s apologetic was that he consistently overemphasized the power of human reason to lead to correct conclusions about ultimate matters. He had some success with this method in a time period that could be called the last gasp of modernity – that is, the tail end of the era dominated by the Enlightenment – but there is little to commend it in most quarters today’ (p. 235). The evangelical presents the following dilemma for Schaeffer (or Edwards): if total depravity is true, then you do not need to give arguments, and if total depravity is not true then you also do not need the intellect because others forms of persuasion are much more effective in getting the desired outcome.

Hankins claims Schaeffer for evangelicalism by noting characteristic strengths and weaknesses in both: ‘In summary, Schaeffer exhibited both evangelicalism’s strengths – a seriousness about culture and ideas and a deep spirituality and emphasis on Christian community – and its weaknesses – overreliance on Enlightenment categories and a tendency to conflate issues of faith with issues of politics and American patriotism’ (p. 238). Perhaps we can gain some insights by considering these aspects of evangelicalism and their focus on the love of God and soteriology seen in Marsden’s study. The weaknesses of relying on Enlightenment epistemology and metaphysics, and conflating faith and politics, is a problem of not knowing how to ‘know’, what is real, and what to do. These are major confusions and perhaps it should be no surprise that if evangelicals are weak in these areas then naturalism will gain the ascendency. If the evangelical response traceable to the first Great Awakening is that one must assume that God exists, that Christ is necessary for salvation from sin, and that this shows the love of God, then consider some of the challenges that will arise.

The initial problem is why begin by assuming one metaphysic (theism) as opposed to another (naturalism, Hinduism, Buddhism)? As soon as one begins offering an argument to justify this, then one is no longer assuming God but instead is at least implicitly claiming that God’s existence must be argued for. Similarly, to assume the reality of sin and the need for redemption from Christ will illicit questions such as ‘what is sin?’ If one defines sin in relation to God, such as breaking God’s laws, turning away from God, displeasing God, one is back to needing to show that there is a God in the first place.

Yet, this need for proof is sidestepped because the focus is not knowing the truth about ‘knowledge, reality, and the good’, but in persuading others to accept Jesus. But this is a problem because ‘accepting Jesus’ is itself wrapped in claims about knowledge, reality, and the good. To defend the practice of focusing on this soteriology from criticisms from other worldviews (like naturalism) by showing that the criticisms are misguided or insufficient is not the same as showing that this soteriology is itself based on what is true about reality. Thus, by assuming the very things that need to be proven, someone can say that people are nonrational and reason is not necessary or sufficient to know God.

However, given the need to know if God exists, and what is the sin that requires redemption, and why this necessitates the death and resurrection of Christ, the claim about Schaeffer (and Edwards) should not be that he focused on arguments and reason too much, but that he needed to go further in that direction. Furthermore, the dichotomy between reason and love/community should be abandoned once and for all. In order to love another, one must know what is good for that other, and so love presupposes reason rather than excluding, or being separate from, reason. Schaeffer was able to love others and establish a community at L’Abri because he knew that the good for others requires a community in which the most important questions can be discussed.

These two judicious biographies can be highly recommended for a number of reasons. They bring two important thinkers into greater focus, and they raise important questions about the history of religion in America and the present challenges that Christianity faces. If the authors bring their own framework into the interpretation of Edwards and Schaeffer, this can be understood not only as difficult to avoid in the work of history, but also as a good example of the contemporary mindset of evangelicals which is in a way a further revelation of the very subject being studied in Edwards and Schaeffer.

Leave a Reply