Normative Ethics

The study of ethics arises in relation to the reality of choice. As we make a choice, we are aware that there were other options and ask ourselves if we…

The First Amendment and Natural Religion

The United States was founded on natural religion. The grievances justifying independence rest on the claim that there are some things self-evident about God and human nature and from these…

Natural Law and Philosophical Presuppositions

This chapter studies the role of general revelation in natural law theory. General revelation, what all persons can know about God and the good provides the foundation of natural law…

Introduction: The Formula of the Declaration of Independence

They say they want the kingdom

But they don’t want God in it.

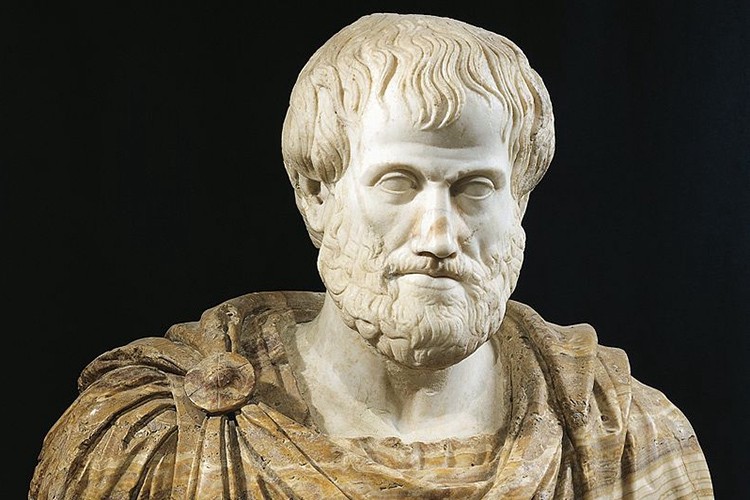

Should we Read Aristotle?

A pastor friend sent me this question:

Should Christians read Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics?

My answer is: yes, read everything. Let me explain why. Aristotle points out something we can all know: our choices are aimed at ends. Some of these ends are intermediate meaning they are aimed at another end. There is a highest or final end. This is called the good. Aristotle tells us happiness is the good. For Aristotle, happiness is not an inner feeling but the condition of living well.

How Aquinas Limits Natural Theology

I have found myself in debates with Thomists who are looking to retrieve aspects of his theology in the combat against open theists and those who make God changeable. When I have suggested that Aquinas does not get us to theism with his natural theology because he does not think we can use reason to show that the universe had a beginning, the standard response is that I have not read Aquinas and don’t understand him. When I quote Aquinas as saying natural reason cannot show that the universe had a beginning, the response surprised me. Rather than acknowledging that perhaps Aquinas is not as strong on natural theology as others (Augustine and Hodge both think we can show that the universe had a beginning), I get a reply that astounds me.

Common Notions and Reason as the Laws of Thought

Replying to a video by Richard Muller about John Owen and Reason

Mins 1-10 and then 53 to end are directly relevant here.

There’s lots of good stuff here, especially about the history of theology and the details of John Owen. I’m glad to see Owen and Muller rejecting the Platonic theory of knowledge. I appreciate that he says unbelievers are given truths but do not respect them as such, meaning they don’t believe them (rather than saying everyone knows), thus avoiding the problem of akrasia. He does good work on arguing against the skepticism behind some forms of tolerance and defending our ability to use reason to know religious truths. My reflections are meant to be constructive to encourage brothers to greater consistency so they have a more piercing witness against unbelief.

A Friendly Reply to Carl Mosser About the Beatific Vision

John 1:18: No man hath seen God at any time, the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him. I appreciate Carl referring…

Natural Theology: Clear and Full or Bare and Minimal?

This is an excellent contribution that will delight students of natural theology. It raises all the right questions that will be highlighted here. Natural theology is the systemized study of general revelation. We can and should study general revelation. That also means we should refrain from settling for unsound arguments that claim to support natural theology. We may find ourselves spending as much time weeding out such arguments as we do giving sound arguments. In this new book on natural theology based on lectures from Vos, J.V. Fesko gives us a 52-page introduction that takes us through an overview of Christian thinking about natural theology. From there, we turn to 93 pages of lecture notes from Vos. Fesko explains many of the standard problems about reason and faith in natural theology: does it get us past generic theism, how can reason operate after the fall, what is its relationship to scripture, and does everyone know God? But perhaps most importantly, he helps indicate a number of ambiguities that plague the discussion about natural theology and result in unsound arguments which tarnish nature theology as an endeavor.

Graham Oppy and Owen Anderson Debate Sin and the Inexcusability of Unbelief

Anderson’s stated aim in this work is to defend what he calls ‘The Principle of Clarity’. In his own words, ‘this principle states that if the failure to know God (unbelief) is inexcusable (culpable ignorance), then it must be clear (readily knowable) that God exists’ (2). Anderson also asserts that he aims to establish that The Principle of Clarity is, necessarily, ‘a presupposition to the redemptive claims of Christianity’ (20).

Anderson holds that Christianity teaches that unbelief is culpable ignorance; indeed, he goes so far as to claim that this is Christianity’s ‘central truth’ (201). Moreover, he claims that Christianity teaches that unbelievers need redemption precisely because they are guilty for their unbelief (3). According to Anderson, unbelief is ‘… the central sin for which Christ died’ (2), ‘… the sin that results in all other kinds of sin, … the “root sin”, … “the original sin”, … “the first sin”’ (42). And he claims that ‘if it is true that unbelief is inexcusable, and justice demands payment for wrong, then the suffering and death of Christ … can be understood’ (79).